Fear of a Muslim Planet

Hip-Hop’s Hidden History

Camoflouged Torahs, Bibles and glorious Qurans

The books that take you to heaven and let you meet the Lord there

Have become misinterpreted, reasons for warfare

We read ’em with blind eyes I guarantee you there’s more there

The rich must be blind because they didnt see the poor there

— Lupe Fiasco, «American Terrorist» (Food & Liquor, 2006).

«Hip Hop and the visibility of Muslim artists offers a way to turn racist paradigms on their head. When rappers rhyme over the azaan or Quran ayaats, mainstream society’s perceptions of an ‘alien’ religion are flipped.»

Transmediale (Berlin) jury’s statement for Villem Flusser Award nominations 2008

Journalist Harry Allen once called Islam «hip-hop’s unofficial religion». This theme is echoed by Adisa Banjoko, unofficial ambassador of Muslim hip-hop, who says: «Muslim influence was at the ground floor of hip hop. Hip hop came from the streets, from the toughest neighborhoods, and that’s always where the Muslims were.» (1) Hip-hop’s Muslim connection came initially via the 5 Percenter sect, and later expanded to embrace Nation of Islam (NOI), Sufi, and Sunni Islam. Since the 1980s, there have also been shifts where 5 Percenters have moved to NOI or Sunni beliefs. The same artists’ back catalog may reflect both his 5 Percenter beliefs and his later NOI faith. Islamic iconography, philosophy, and phrases are in fact so widespread in hip-hop, they show up regularly even in the works of non-Muslim rappers.

In spite of this pioneering and continuing role, Islam as a cultural force in hip-hop is severely under-documented. In the most recent oversight, Jeff Chang’s exhaustive hip-hop history «Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop» (Picador, 2005) pays only fleeting attention to the Muslim connection. Elsewhere in mainstream media, the Muslim connection is never spoken aloud, even in the middle of thorough analysis and journalism. Ted Swedenburg calls this «almost willful avoidance.» In this, there are parallels to the larger invisibility of black Muslims, who have been shut out of many conversations about the role of Islam in America.

This deliberate invisibility mirrors America’s continuing unease with Islam. Black Muslims and hip-hop are frozen out of the larger debate over Islam because they would problematise the entire conversation. If we acknowledge that the largest segment of American Muslims are black Americans, it makes it more difficult to stereotype Muslims as «immigrants» or «outsiders». Furthermore, if we look at Muslim anger and see within it a portion that is African-American, we are forced to confront an indictment of American society. This is a viewpoint that the music press has assiduously avoided. Finally, the idea of Islam as a obscurantist force rubs against its positive influence within hip-hop. Hip-hop scholars have not been able to absorb or observe the Muslim role in creating unique rhyme flows and politically conscious hip-hop. Safer perhaps to avoid the topic.

Born Muslim, Born Black? (2)

A dominant discourse links American Islam to Arabs and South Asians, considered new arrivals to America’s shore. But statistics tell a contradictory story. According to research presented by the American Muslim Council (AMC), in 1992, between 5 to 8 million Americans followed some variation of the Islamic faith. (3)

AMC calculated the largest bloc of Muslims to be African-Americans at 42 percent. If African immigrants are included, the number goes up to 46 percent. South Asians are the next highest at 24 percent. Only 12 percent of American Muslims are of Arab descent (majority of Arab-Americans are Christian). Looking at subsections within the black population, we find the proportions even higher: 30 percent of African-Americans in the prison system are Muslim, many of whom convert after incarceration — following the trajectory of Malcolm X and Imam Jamil Al-Amin (formerly H. Rap Brown).

There are many reasons why Islam has been popular among African-Americans from the beginning. Scholars point to the roots of Islam within the original slave populations. Silviane Diouf calculated that «up to 40 percent» of the Atlantic slave trade was Muslim. (4)

Although much of the original belief systems were wiped out in the period leading up to the Civil War, residues have transmitted themselves through the black experience and the popular imagination. An example of this emerges in Michael Muhammad Knight’s punk Muslim novel The Taqwacores (Autonomedia, 2005), when one character says: «There’s an old jail in the Carolinas where they used to bring slaves right off the ships … It’s still there, it’s like a tourist spot now. But anyway, there’s ayats from the Quran on the wall, like two hundred years old, still right there».

All of this helped create a perception within the black community that Islam was not an alien religion. Rather it was seen as something that was «lost-found.» James Baldwin diagnosed this accurately in «The Fire Next Time»:

«God had come a long way from the desert — but then so had Allah, though in a very different direction. God, going north, and rising on the wings of power, had become white, and Allah, out of power, had become — for all practical purposes anyway — black.» (5)

[…]

How Islam Birthed Hip-Hop

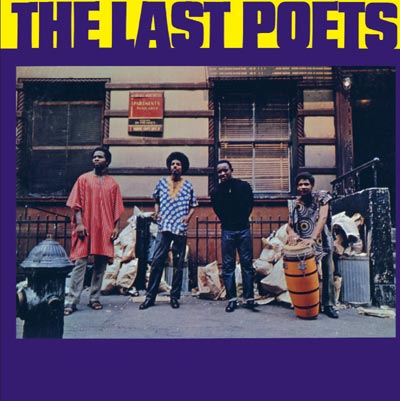

Although the usual answer to «who invented rap» is the trio of DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa, and Grandmaster Flash, the roots extend further back to black Muslim artists experimenting with rhyme structure and spoken word delivery in the 1960s. One of the earliest influences was the group The Last Poets, whose founding members included Abiodun Oyewole, Umar Bin Hassan, Jalal Nurridin, and Suliman El Hadi. The Poets were black radicals, detonating their lyrics on an America already on fire:

When the revolution comes

some of us will catch it on TV

with chicken hanging from our mouths

you’ll know it’s revolution

because there won’t be no commercials

when the revolution comes

In their most famous spoken-word piece «Niggers are Scared of Revolution», they pioneered the staccato speeded-up delivery that came to characterise rap rhythms. Simultaneously, this work began the re-appropriation of the «N» word, a process now done to death by modern hip-hop:

Niggers are scared of revolution but niggers shouldn’t be scared of revolution because revolution is nothing but change, and all niggers do is change. Niggers come in from work and change into pimping clothes to hit the street and make some quick change. Niggers change their hair from black to red to blond and hope like hell their looks will change.

The Last Poets were the original activist-artists, combining their music and poetry with direct action — including alliances with the SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee), the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), and the Black Panthers. Their records were released during a period of violent confrontation, including the murder of two black students and the wounding of twelve others by police at Jackson State University, a daisy-chain of ghetto rebellions in 1970, and the FBI’s national campaign to arrest Angela Davis. With their lyrics feeding into the fervor of the times, the Poets were heavily monitored by the FBI and police, and were arrested for trying to rob the Ku Klux Klan. Decades later, these same trends were repeated as the NYPD began surveillance of hip-hop groups, especially those with outspoken politics.

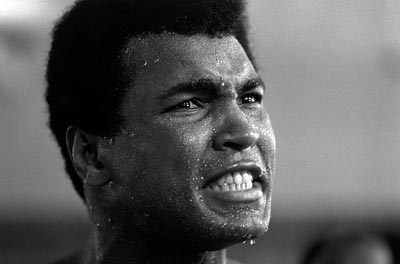

[…] Similarly influential, though in a different vein, was the newly converted Muhammad Ali. By dropping his «slave name» of Cassius Clay for Muhammad Ali («I don’t have to be what you want me to be; I’m free to be what I want»), and replacing his cry of «I am the Greatest» to «Allah is the Greatest», Ali became the most visible Muslim in America and a hero of the Afro-Asian and Islamic world. He was in the mould of the defiant black men — Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, Gabriel Prosser, Jack Johnson, and Paul Robeson. The difference was that his Muslim faith was a key aspect of his righteous rage and political defiance. Ali’s refusal to fight in Vietnam, coupled with incendiary comment «No Viet Cong never called me a nigger», enshrined his rebellion in the black psyche.

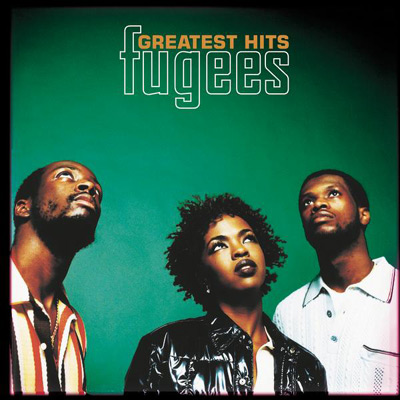

Ali’s rebellious spirit was also in his poetry, which led George Plimpton to conclude that «his ability to compose rhymes on the run could very well qualify him as the first rapper». (6) Recognising Ali’s Singular contribution to both Islam and the black male image, Ali’s artistic descendants later sang:

The man’s got a God complex

But take the text and change the picture

Watch Muhammad play the messenger like Holy Muslim scriptures

Take orders from only God

Only war when it’s Jihad

— Tribe Called Quest, Fugees, et al., «Rumble in the Jungle» (When We Were Kings)

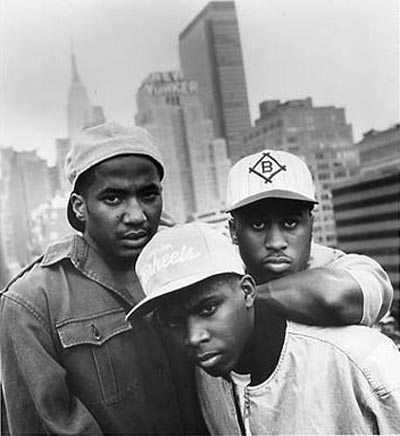

[…] As socially-conscious rap began to come out in the 1980s, NOI’s politics also spread into songs. In 1983, Keith Leblanc released «No Sell-Out», dubbing a Malcolm X speech into the mix. This was the beginning of political rap’s obsession with Malcolm, sampling him hundreds of times throughout the 1980s and 90s. Setting the gold standard for such rap was the group Public Enemy (below). In this, band member Professor Griff’s strong NOI beliefs played a key role. When they appeared in battle fatigues, a cocktail of Fruit of Islam and Black Panther, White America was terrified by the spectre of revived race riots. The media promptly dubbed PE the «most dangerous band alive», which they scornfully attacked in lyrics:

The follower of Farrakhan

Don’t tell me that you understand

Until you hear the man

The book of the new school rap game

Writers treat me like Coltrane, (7) insane

— Public Enemy, «Don’t Believe the Hype» (It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, 1988)

Public Enemy’s path was followed by KRS-One, who preached politics and black self-empowerment through Boogie Down Productions. Unlike later 5 Percenters like Wu-Tang, KRS-One stayed clear of numeric theory in favor of more conscious politics:

But last but not least racial prejudice

Is the black man speakin’ out of ignorance

Whitey this and Ching-Chow that

Is not how the intelligent man acts

You can’t blame the whole white race

For slavery, cos this ain’t the case

— Boogie Down Productions, «The Racist» (Edutainment, 1990)

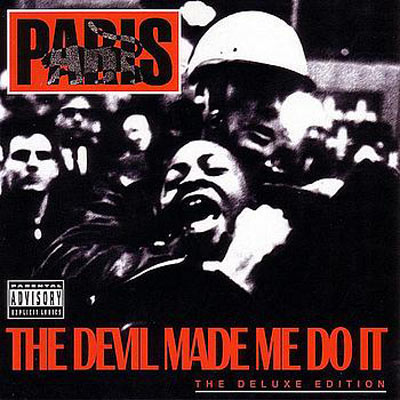

Kevin Powell has described the 1987-1992 era as the «golden age of hip hop». (8) In this period of restless activity, Sunni Muslims also began to enter the scene. Most notable was Tribe Called Quest (with Sunni followers Q-Tip and Ali Shaheed Muhammad) preaching Afrocentric awareness, collective love, and peace. On the other side of peace was the raw defiance of Paris. His work reflected a mixture of Sunni Islam and Panther ideology, as in his famous song:

Revolution ain’t never been simple

Following the path from Allah for know just

Build your brain and we’ll soon make progress

Paid your dues, don’t snooze or lose

That came with the masterplan that got you

So know who’s opposed to the dominant dark skin

Food for thought as a law for the brother man

— Paris, «The Devil Made Me Do It» (The Devil Made Me Do It, 1990)

Paris, «The Devil Made Me Do It»

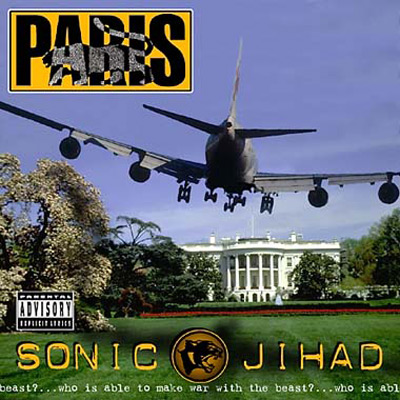

While the Afrocentric messages of Tribe were celebrated, the aggressive music of Paris scared tastemakers. The Devil Made Me Do It carried the iconic photo of a Black boy in a chokehold by riot police. Record stores refused to carry the album, citing its cover art. Paris’ 1992 album, Sleeping with the Enemy, carried a photo of him holding a machine gun, hiding behind a tree on the White House lawn. Shareholder pressure over the song «Bush Killa» forced Time Warner subsidiary Tommy Boy to drop the record. After a five-year hiatus, his follow-up album Sonic Jihad (with the infamous image of a plane flying into the White House) was released on his own label. Reflecting ruefully on the commercial price of radical politics, Paris’ website notes, «his uncompromising stance on political issues and biting social commentary have both aided and hindered his quest to bring solid music and messages to the masses.» (9)

While Paris is a casualty in the battle over lyrics, many other Muslim artists have risen to become giants of the scene. These include 5 Percenter-influenced Busta Rhymes, Wu-Tang Clan, Big Daddy Kane, Brand Nubian, Nas, Gang Starr, Mobb Deep, Poor Righteous Teachers, Queen Latifah and Ladybug Mecca (Digable Planets); Sunni artists Jurassic 5, Mos Def, Roots (who also have 5 Percenters as members), Kool Moe Dee, and Everlast; NOI-influenced MC Ren, Da Lench Mob, Ice Cube, Kam, and K-Solo; and other artists with more fluid affiliations, such as Eve, Common, Brother Ali, Intelligent Hoodlum, Afrika Islam, Daddy O (Stetsasonic), and Jeru the Damaja. Coming up fast are the next generation of Muslim rappers, who are tipped toward the Sunni scale and include some South Asian and Arab rappers. […]

Deep in the Flow

The initial link between Islam and hip-hop came via 5 Percent. This came through its focus on wordplay, numerology, and race theory. This trajectory was paralleled by the Nation of Islam, which embraced rap as a preaching tool at a time when the black Christian churches rejected it. Conscious rappers also gravitated toward NOI because its confrontational politics fit with their fierce rhymes. Beyond these initial connections, there were other reasons why Islamic thought influenced rappers. H. Samy Alim has researched the structural and symbolic similarities between hip-hop rhymes and Quranic text. (10)

Through interviews with Muslim rappers, he has uncovered a key parallel. The Quran was revealed to the Prophet Mohammed through an oral tradition, using melodic prose. In this, there are parallels to hip-hop’s birth as a means of empowering inner-city griots to transmit stories of urban blight and chaos via rhyme and flow.

[…] Taking the analogy further, Common anoints hip-hop as the new vehicle for reaching people with Allah’s message. Although orthodox preachers would dismiss this as shirk (blasphemy), Minister Farrakhan’s embrace of hip-hop is clearly inspired by sentiments such as:

The perseverance of a rebel I drop heavier levels

It’s unseen or heard, a king with words

Can’t knock the hustle, but I’ve seen street dreams deferred

Dark spots in my mind where the scene occurred

Some say I’m too deep, I’m in too deep to sleep

Through me, Muhammed will forever speak

— Common, «The 6th Sense» (Like Water for Chocolate, 2000)

Speaking of the use of metaphor in hip-hop, Bay area rapper JT the Bigga Figga draws an analogy between the creation of black street argot and the creative use of language in the Quran to reach believers.

[…] Of course, not all strands of Islam accept parallels between hip-hop and Quranic recitations. To more orthodox sects, the Quran, the Surah, and the Azaan are all meant to be chanted (tilawa) which can be argued to be different from singing (ghanniya). These rigid structures break down across generational lines, with yoounger people embracing hip-hop as a boost to their understanding of Islam. Eman Tai, member of the Calligraphy of Thought spoken-word collective, connects hip-hop to Islam’s history: «It’s part of our history and culture in Islam. The traditional books of law and philosophy in Islam were written in poetry, and students memorise them with drums, basically singing out the poetry. And if you ‘beat’ that up, it sounds just like rapping». (11) Beyond a focus on scripture and philosophy, Muslim beliefs guide rappers in very specific ways toward community renewal and progressive politics. NOI focuses on self-sufficiency of the community and this has come to influence the lyrics of rap’s Muslim generation. When NOI first moves into a blighted area, they get people dress well, stop drinking, and clean up crack houses. Then come related programs, such as the push to buy black and boycott racist merchants. All of these programs influenced rap lyrics that sought to uplift the race. But here the contradictions of the music also come bubbling to the surface. When Wu-Tang began their Forever double album, the lyrics embraced their Muslim listeners:

These things just took over me

Just took over my whole body

So I can’t even see no more

I’m calling my black woman a bitch

I’m calling my peoples all kinds of thing that they not

I’m lost brother, can you help me

Can you help me brother, please

— Wu-Tang Clan, «Wu-Revolution» (Forever, 1999)

But within the space of one song, the listeners face the contradiction of a «smoking, drinking, fornicating» life:

Bitch ass niggaz counterfeit the funk

I smoke the bead and the skunk, tree top of the trunk

Moonshine drunken monk, Ya HEAD, get shrunk

The touch of skunk, I be bedding bitches by the chunk

— Wu-Tang Clan, «Reunited» (Forever, 1999)

Wu-Tang Clan is a constellation of artists, and some members (like the late Ol’ Dirty Bastard who sang the second set of lyrics) were either not Muslim, or «struggling to find the path». Typically when talking about «misguided» Muslim rappers, the critics focus on 5 Percenter belief as a source for some of these mistakes. This creates new intra-sect tensions between Muslim rappers.

As Muslim as They Want to Be

From the very beginning, the 5 Percenter sect was particularly skilled at creating iconography that appealed to inner-city youth. The school established in Harlem in 1967 was the «Allah School in Mecca», and the five points of the constellation were «Mecca» (Harlem), «Medina» (Brooklyn), «The Desert» (Queens), «Pelan» (Bronx), and «New Jerusalem» (New Jersey). Tracts of 5 Percent concepts were initially circulated as Xeroxed pamphlet «lessons» that passed from hand to hand. But as early hip-hop artists started incorporating 5 Percenter theology into freestyle rhymes, pamphlets were superseded by the more powerful oral tradition. Rappers, beatboxers, and DJs, became preachers, spreading the theology at the speed of music. Key portions of their theories spread through rap lyrics, including black man as Allah («Praises are due to Allah, that’s me» — Poor Righteous Teachers), the Chosen 5 Percent («Why? That’s most asked by 85» — Ladybug Mecca/Digable Planets), supreme mathematics and the supreme alphabet («Now I’m rolling with the seven (12) and the crescent» -- Digable Planets), racial separatism («No blue eyes and blonde hair is over here» -- Poor Righteous Teachers), and the breaking of words into components («U-n-i-verse — you and I verse» -- Roots). In addition, 5 Percenters were the innovators behind early hip-hop slang, including «’sup, G?» (originally «G» meant God, not gangsta), «Word is bond», «Break it down», «Peace», «droppin’ science», and «represent».

[…] As this debate unfolds within hip-hop, Daulatzai’s more nuanced understanding of race, class, and music is reflected among other American Muslims as well. There are now hip-hop fans willing to engage in ijtihad (debate) about 5 Percenters.

Even Banjoko seems to have softened his stance toward 5 Percenters in recent years. He told me recently, «I still disagree with their beliefs. These guys piecemeal their theology to the nth degree. You’ll have these pseudo Wu-Tang affiliates who talk absolute berserk madness. But in spite of theological flaws, they have still been a positive force and I can’t deny that. One benefit of the 5 Percenters is that through them, inner-city kids are at least becoming familiar with Islamic terms». (13)

Generation M

One of the most overused phrases is «after 9/11». Yet we can at least say that the new realities have brought a change to Muslim hip-hop. For Muslim youth, there were two new forces in their lives. First, there is the crackdown on Muslim civil liberties, expressed through the Patriot Act, INS deportations, «special registrations», «extraordinary renditions», no-fly lists, and torture memos. Second, there are the continuing U.S. wars of occupation in Afghanistan and Iraq.

All this has inspired the rise of new Muslim-identified hip-hop bands. Many of these are now Sunni affiliated and some are led by children of Muslim immigrants. Hip-hop remains the singular voice of black America, but that core is now made larger by Arab, Asian, African, French, and British Muslims. The center for these new networks is the Internet, especially through websites like ‹MuslimHipHop.com› and ‹Muslimac.com› (Muslim Artists Central). Among the many they host, the up-and-coming names include Capital D, Sons of Hagar, After Hijrah 11:59, Arab Legion, Divine Styler, Halal Styles, Iron Crescent, Jamil Mustafa, Kenny Muhammad, Mujahideen Team, Native Deen, the Hammer Bros., the Iron Triangle, and Young Messengerrzz.

Taking on a more assertive Muslim identity, many of these new artists identify as «Generation M». Unlike the 5 Percenters’ fluid definitions, they adhere to a more traditional Islamic view and multiracial identity. In their lyrics, many of the concerns are about being Muslim in the West and the current civil liberties environment. Sons of Hagar, one of the rising stars, asserts a strident Arab identity:

My own country is trying to get rid of me

Got no shoulder to lean on and I ain’t crying neither

It’s the Arab hunting season

And I ain’t leavin

— Sons of Hagar, «INSurrection» (A Change, 2004)

Just as Islamophobia is now a global trend, the critiques of that force come from all corners of the world. Sons of Hagar are joined by Paris, who raps:

See me blame it on a foreigner and non-white men

Celebrate my gestapo with a positive spin

Then manipulate the media — it’s US first

Get the stupid-ass public to agree with my words

— Paris, «Evil» (Sonic Jihad, 2003)

Paris is echoed by the Asian Dub Foundation’s British-Bangladeshi vocalist, who links blowback to US-Taliban alliances:

Babylon is really burning this time

coming home to roost on a Soviet landmine

Climbing out the subway burning eyes spinning head

Walking through the station breaking into a cold sweat

Is the ticking time bomb in my head or your bag

Have you been snorting white lines with President Gas

Crawling from the wreckage of my tumblin’ tower block

Someone else had to finish the job

It was the enemy of the enemy

The enemy of the enemy

He’s a friend

Til he’s the enemy again

— Asian Dub Foundation, «Enemy of the Enemy» (Enemy of the Enemy, 2003)

In the 1990s, Public Enemy surveyed a landscape of police brutality, a crack epidemic, and hostile Reaganomics, and unleashed their rage on the mic. Public Enemy’s grand project to channel «Black CNN» into a united political movement foundered on Professor Griff’s anti-Semitism. Ten years later, «Driving While Black» has been switched for «Flying While Brown» and the fight back is also in rhymes. The media played a crucial role in PE’s downfall, paving the way for the apolitical bling stylings of gangsta rap and an eternal cycle of Hot 97-generated «beefs». With Generation M, some will be equally ready to seize on any missteps and derail the political mission. Guarding against the media glare, while building a deep-rooted Muslim hip-hop movement, where the black experience is core, is the next project for activist-academics like Daulatzai and Banjoko.

Last/Lost Words

In the ongoing debates over Islam, the same South Asian and Arab faces are always brought out. It is always Fareed Zakaria, Fouad Ajami, Imam Feisal, et al. African American Muslims remain the invisible minority in the public eye. Part of this can be attributed to the continuing phobia against Nation of Islam. (14) But the sidelining of black Muslims is also part of the larger project to render Muslims as permanent «outsiders». African Americans complicate the narrative because they are not immigrants. Nor do they have an origin country where they can be deported in times of crisis.

[…] When a black Muslim musician critiques foreign policy or xenophobia, it is still an «angry Muslim voice», but not one that can be easily stereotyped. Hip-hop and the visibility of Muslim artists offers a way to turn racist paradigms on their head. When rappers rhyme over the azaan or Quranic ayaats, mainstream society’s perceptions of an «alien» religion are flipped. Enhanced visibility through music can create a dynamic that moves America from hyper-Islamophobia to a dialogue among equals.

(1) Interview, March 23, 2005.

(2) A play on Suheir Hammad’s Born Palestinian, Born Black (Writers and Readers Publishing, 1996).

(3) These statistics were calculated before a new wave of immigration from Muslim countries probably boosted these numbers. To take one example, according to a 2005 census report, the fastest-growing New York migrant group between 1990-2000 were Bangladeshis. Therefore, it is safe to say these numbers have gone up. At the same time, post-9/11 immigration crackdown and worsening of Muslim civil liberties would dampen these numbers.

(4) Sylviane A. Diouf, Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas (New York University Press, 1998).

(5) James Baldwin, «The Fire Next Time» (Dell Publishing, 1977).

(6) Time Magazine, «Time 100: The Most Important People of the Century» ‹http://www.time.com/time/time100/index_2000_time100.html›

(7) Here PE may also be linked to John Coltrane’s Muslim connection, via Ahmadiya Muslims such as Yusuf Lateef.

(8) Kevin Powell, quoted in Manning Marable, «The Politics of Hip Hop», Along the Color Line, March 2002.

(9) ‹http://www.guerrillafunk.com/paris/bio›

(10) H. Samy Alim, «Exploring the Transglobal Hip Hop Umma», in Muslim Networks: From Hajj to Hip Hop, ed. Miriam Cooke and Bruce B. Lawrence (University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

(11) Marian Liu, «Hip-Hop’s Islamic Influence», SJ Mercury News ‹http://www.daveyd.com/commentaryhiphopislam.html›

(12) A focus on numerology can also be found in Islam — such as the belief that some elements in the Quran are divisible by seven, in a manner impossible to produce without divine intervention.

(13) Interview, March 23, 2005.

(14) On a Long Island TV show called The God Squad, I was asked by a worried host, «Now when you say black Muslims, I just want to make sure you’re not talking about Nation of Islam».

text (extract): originally published in Sound Unbound: Sampling Digital Music and Culture (MIT PRESS, 2008), edited by Paul D. Miller. The essay was short-listed for the Villem Flusser Theory award, Berlin.

picts: www

Fear of a Muslim Planet

RELATED WEB SITES

→ Naeem Mohaiemen’s web site

→ Full text version : PDF

[ Abou Naddara ]

[ Accessible Approach ]

[ Beyrouth ]

[ Cairo as Canvas ]

[ Dawam al hal min al muhal—No Condition is Permanent ]

[ De Montmorency à Metz ]

[ Dowry No ]

• Fear of a Muslim Planet •

[ Fragmented Letters ]

[ Gentle Wall project ]

[ Images and Images ]

[ Kafranbel ]

[ Leading a Smart Revolution ]

[ Lens of a young Person ]

[ Muraqabet amel jidariya—Watching the Creation of a Wall Painting ]

[ No Holy Cows ]

[ On Graphic Crimes and Visible Fractures ]

[ on going ]

[ PMS = Poster Message Service ]

[ Réconciliation ]

[ Rasael—Messages ]

[ Seipone ]

[ T.W.B.T.C ]

[ This is a picture book ]

[ Vitry ]

[ What remains and Things to come ]

FEATURED THEME ON CITY SHARING

by ASUNCION MOLINOS GORDO

-

This project is an instrument for common critical analysis to help understand the reasons behind Egyptians’ diminishing …

by INAS HALABI

-

The project Letters to Fritz and Paul focuses on the expeditions of the Swiss cousins, lovers and scientists, Fritz and …

by SARAH BURGER

-

The planned modern city of Brasilia attracted me since a long time. Her defined shape, location and function proceded he …

by ADRIEN GUILLET

-

Youri Telliug talks with the artist Adrien Guillet about his project Citracit

Youri Telliug - What is Citracit …

by NIGIST GOYTOM

-

In 2013 more than 45 million people have been forced to leave their homes. This amounts to the biggest number of refugees …

by SULAFA HIJAZI

-

The on going debate on Arab identity and its (cultural) representation is strongly shaped by Edward Saidʼs formative …

by ASUNCION MOLINOS GORDO

-

WAM is a site-specific work that uses the historical trope of the cabinet of curiosities to explore the introduction of …

MORE CONTRIBUTIONS BY THE FOLLOWING